By Chris Bruen

Chris Bruen is Senior Director of Research, with primary responsibility for aiding in and expanding upon NMHC’s research in housing and economics. Chris holds a bachelor’s degree in Finance from The George Washington University and an M.S. in Economics from Johns Hopkins University. He can be reached at cbruen@nmhc.org.

The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model recently made headlines for its forecast (made on March 3, 2025) of -2.8% annualized GDP growth for the first quarter of 2025, marking a drastic downward revision from its February estimate of +3.9% growth for the quarter (the GDPNow model has since revised its estimate to -1.8% first quarter growth). For context, the U.S. economy hasn’t experienced negative quarterly growth (contraction) since 1Q 2022.

The Atlanta Fed is not the only institution that attempts to forecast GDP growth, of course. In fact, other models anticipate positive first quarter growth. Yet, these estimates continue to trend downward over uncertainty around tariffs/trade wars and declining consumer confidence1. For instance, the New York Fed Staff Nowcast model is currently forecasting +2.7% annualized GDP growth for the first quarter, down from the model’s prior forecast of 3.1% on Feb. 7, 2025, while Goldman Sachs in early March cut its estimate for 1Q growth from 2.4% to 1.7%.

Tumbling financial markets also reflect economic uncertainty and a growing risk of recession—the NASDAQ fell 9.2% between January 24 and March 24, while the S&P 500 fell 5.7% during this period.

1The Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index fell 7.0 points in February, representing the largest one-month drop since August 2021. University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment also fell for the third consecutive month in March, down 27.1% from the previous year.

What Would a Recession Mean for the Apartment Industry?

The impact a recession would have on the apartment industry ultimately depends on its severity.

The Great Recession, for example, was especially severe and drawn out, spanning from December 2007 to June 2009. During this time, U.S. real GDP declined by more than 4%, while the unemployment rate rose from 4.7% in November 2007 to a peak of 10.0% in October 2009.

This sharp pullback in economic activity translated to increasing apartment vacancy rates, negative rent growth, and negative returns to apartment investors (see Figure 1 and 2 below).

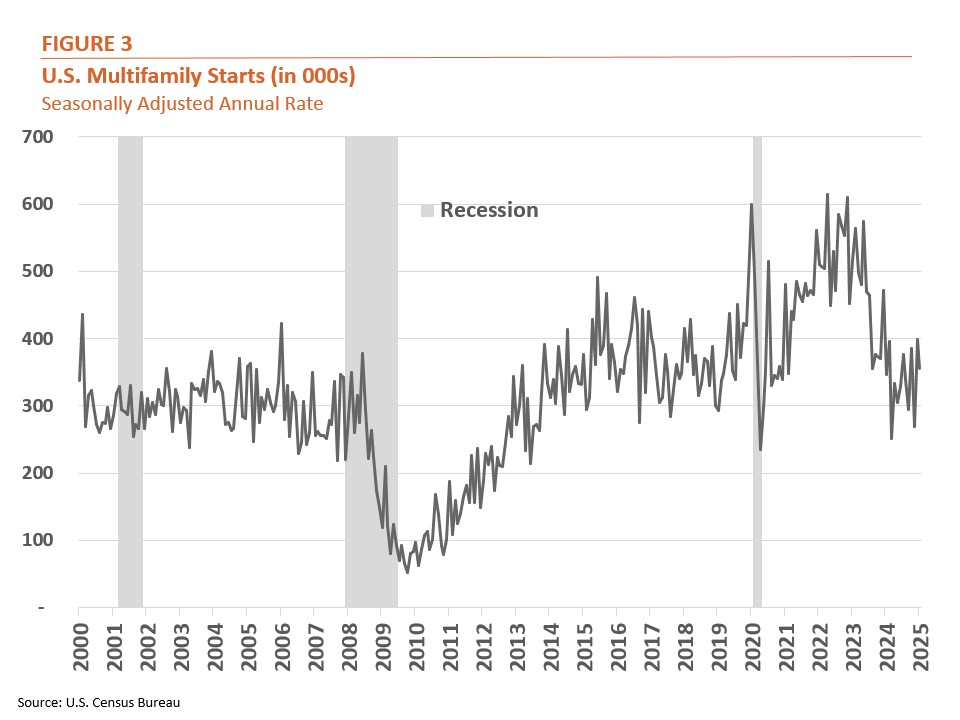

On the construction side, multifamily starts ground to a halt, decreasing by 63.4% in 2009 alone (Figure 3). Even after the recession ended, multifamily construction took years to return to previous levels, contributing to a growing shortage of homes. According to a study from Hoyt Advisory Services, this underproduction of housing resulted in a loss of 4.7 million affordable apartments (monthly rents less than $1,000) from 2015-2020, exacerbating our nation’s affordability crisis.

Annual apartment rent growth2 tracked by CoStar fell from 4.5% in 1Q 2007 to -4.1% in 4Q 2009; the vacancy rate also rose from 6.8% to 7.8% during this period. The COVID-19 recession caused annual rent growth to moderate from 3.4% in 4Q 2019 to 0.5% in 3Q 2020, remaining marginally positive.

The total, unlevered return for apartment investors fell to -8.3% in 2008 and -2.0% in 2009, according to data from NCREIF. Total annual returns to apartment REITs slid to -20.7% in 2007 and then to -28.4% in 2008.

The COVID-19 recession once again caused REIT returns to fall into negative territory (-24.1% as of 3Q 2023), whereas unlevered returns tracked by NCREIF moderated but remained positive.3

The COVID-19 Recession caused multifamily starts to decrease in the short-term. However, the increasing prevalence of remote work during the pandemic led to a shift in demand to more affordable markets with fewer regulations around building, causing multifamily construction to increase to their highest levels in decades in subsequent years.

While the more recent COVID-19 Recession was severe—causing real GDP to fall by an annualized rate of 28.1% in 2Q 2020 (the largest quarterly drop on record) and the unemployment rate to reach double digits for four consecutive months in 2020—it was also very short lived, lasting just two months.

The COVID-19 Recession also coincided with lower rent growth, apartment returns, and construction activity, though not nearly to the same extent as during the Great Recession.

2 Effective asking rents.

3 Returns to REITs tend to be much more volatile and of a higher magnitude compared to NCREIF returns, since they incorporate leverage and are based on values determined in a public market.

Policy Responses

While the federal government and Federal Reserve often pursue stimulative policies to mitigate the severity of recessions, they typically try to ensure that such measures don’t result in elevated levels of inflation.

Because the Great Recession was accompanied by stable prices and even a brief period of deflation, with consumer prices (CPI) decreasing 2.1% between July 2008 and July 2009, the U.S. government and central bank were able to respond proactively to the economic slowdown without generating much inflation (core inflation averaged just 1.9% annually in the decade from 2010 through 2019).

- Fiscal policy response (actions taken by the federal government): the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 introduced nearly $1 trillion worth of stimulus into the U.S. economy.

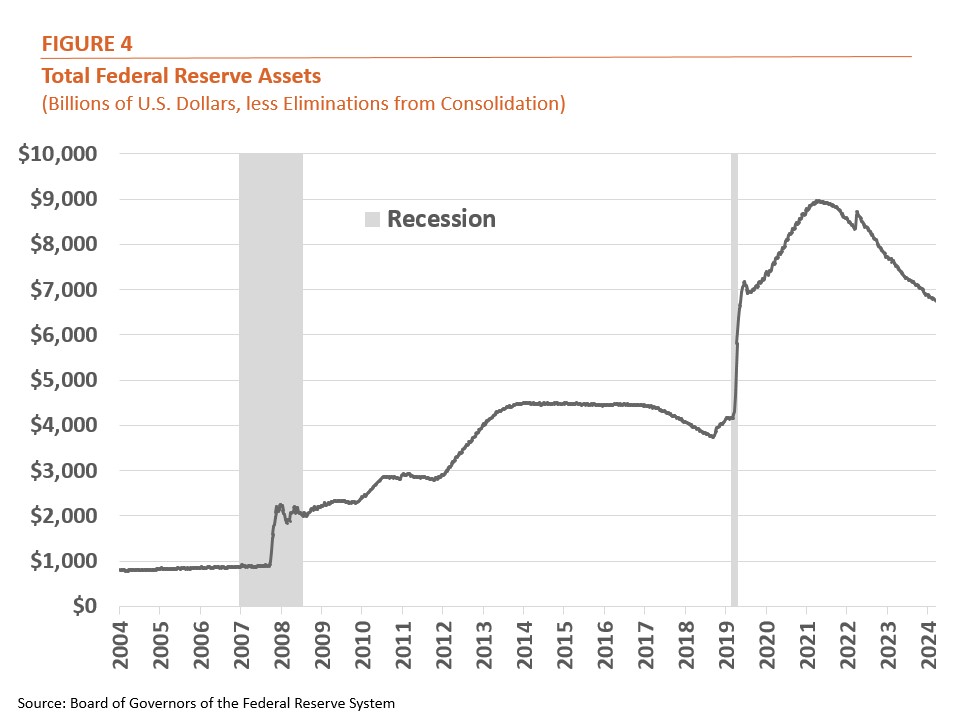

- Monetary policy response (actions taken by the central bank): the Federal Reserve lowered its federal funds rate to zero in 2008 (a target range between 0 and 0.25%) before spending billions of dollars on longer-term asset purchases over the following decade.

The COVID-19 recession posed a more challenging set of circumstances for policy makers, since the pandemic caused a severe disruption to global supply chains. This supply chain disruption caused inflationary pressure at precisely the same time that the government and Fed sought to stimulate the economy and mitigate the recession’s severity. This time around, unprecedented fiscal stimulus coupled with accommodative monetary policy—while effective in restoring economic activity—came up against a limited supply of goods, resulting in the highest rates of inflation since the early 1980s.

- Fiscal policy response: the federal government provided trillions of dollars in fiscal stimulus in response to the COVID-19 recession, which can be seen in Figure 4 below.

- Monetary policy response: the Fed once again lowered its short-term interest rate to zero and began its fourth round of quantitative easing, expanding the size of its balance sheet by nearly 30% between March 2020 and April 2021.

These two case studies illustrate how inflationary pressures can compromise the ability of the federal government and the Federal Reserve to effectively counteract an economic slowdown or recession. The slow recovery and low inflation associated with the Great Recession suggests that the federal government could have perhaps done more in the way of fiscal stimulus, while the short duration of the COVID-19 recession and subsequent inflation point toward the opposite—that the federal government’s stimulus (despite its efficacy) may have cost consumers some purchasing power.

Current Risks of Stagflation

What makes current recessionary risks especially dangerous is the parallel increase we’re seeing in inflation expectations.

Headline inflation, measured by the consumer price index (CPI), came in at 2.8% in February – still well above the Fed’s target of 2% – with many consumers and businesses anticipating even more rapid price increases over the coming year:

The University of Michigan’s Surveys of Consumers shows median year-ahead inflation expectations rising from 2.6% in November 2024 to 2.8% in December, 3.3% in January, and 4.3% in February.

Respondents to the Consumer Confidence Survey reported forecasts of steeper price increases, with average 12-month inflation expectations rising from 5.2% in January to 6.0% in February.

The New York Fed Survey of Consumer Expectations has shown less upward movement – its median estimate of year-ahead inflation increasing just 10 basis points (bps) to 3.1% in February.

Conclusion

Slowing economic growth and rising inflation is a dangerous combination which, in the worst-case scenario, can lead to the dreaded “stagflation”—economic contraction in the presence of rapidly rising prices—a phenomenon not seen since the 1970s.

In this scenario, the Federal Reserve must choose between conflicting objectives of low inflation (typically a 2% target) and full employment. In 1979, for instance, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker chose to raise interest rates drastically, causing a recession but also ushering in a prolonged period of low inflation. It’s unclear if Chairman Powell would similarly prioritize low inflation over employment. It’s also unclear whether the current Trump administration—which has prioritized cutting government expenditures—would reverse course in the event of a recession.

Questions or comments on Research Notes should be directed to Chris Bruen, NMHC Sr. Director of Research, or NMHC Research Analyst, Ryan Hecker.