Given the highly contagious nature of COVID-19 and the medical community’s recommendations around social distancing, there is increasing discussion around whether dense urban environments are more susceptible to the spread of disease. A recent study from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health failed to find a causal link between density and COVID-19 infection or death rates; however, there is other evidence (NYU Furman Center; CalMatters) that individuals living in more crowded housing units are more likely to contract the virus.

In this Research Notes, we examine the areas of the U.S. that have the highest rates of household crowding and, thus, might be at a greater risk of spreading COVID-19. In addition, we also explore the degree to which a lack of affordable housing might be driving these higher rates of crowding. In summary, we find that a variety of demographic and economic factors influence crowding, but that those individuals living in less affordable markets appear more likely to live in more crowded housing arrangements, potentially increasing their risk of exposure to the virus.

Differentiating Between Density and Crowding

The density of an area refers to its concentration of either people (population density) or households (household density). For example, Figure 1 below charts the number of households per square mile of every U.S. Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA; Census areas containing at least 100,000 people).

Unsurprisingly, New York City is home to many of the densest neighborhoods in the U.S. During the 2014-2018 period, the Upper East Side neighborhood recorded 55,597 households per square mile, followed by Murray Hill, Gramercy & Stuyvesant Town (48,835 households per square mile) and the Chinatown and Lower East Side neighborhoods of Manhattan (41,117 households per square mile). For some perspective, the densest PUMA outside the New York metro area was the Central/Koreatown area of Los Angeles, with 15,467 households per square mile.

Yet, when we look instead at household crowding—the average number of persons per room of PUMA households—a much different picture emerges.

Nine of the top 10 PUMAs with the highest levels of crowding were either in Los Angeles or Orange Counties, Calif., with the Elmhurst and South Corona neighborhoods of Queens being the sole representative from New York City. This suggests that high levels of density do not necessarily translate to high levels of crowding. For example, the Upper East Side of New York, which we recognized as the nation’s densest PUMA, recorded an average of 0.50 persons per room, only slightly above the national average of 0.48, whereas Southeast and East Vernon, LA City – with a density of 5,104 households per square mile – had a significantly higher crowding rate of 0.91 persons per room, on average.

Furthermore, Figure 3 below illustrates that there is no obvious correlation between the density and crowding of areas.

Household Crowding in Immigrant Households

Aside from density, a number of demographic factors might help explain why some areas have higher levels of crowding than others. For instance, a 2007 study commissioned by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) showed that overcrowded households (which they defined as households with more than one person per room) were more prevalent among residents who were born outside the U.S. This is likely due to the greater propensity of foreign-born populations to live in multigenerational households, as some research has shown. For this reason, it is reasonable to expect that households consisting predominantly of foreign-born members would tend to have a higher average number of persons per room.

Our research also finds that households with U.S. born householders tend to have a lower level of household crowding and, furthermore, that there are differences by place of birth for households with foreign-born householders. For instance, from 2014-2018, U.S.-born householders lived in households with an average of 0.44 persons per room; householders hailing from Canada, Europe or Australia tended to live in similar sized households (0.47 persons per room, on average). Householders who were born in Central America, South America of the Caribbean, on the other hand, lived in households with an average of 0.76 persons per room; for those born in Africa, an average of 0.67 persons per room; the Middle East, 0.65 persons per room; and, Asia, 0.64 persons per room.

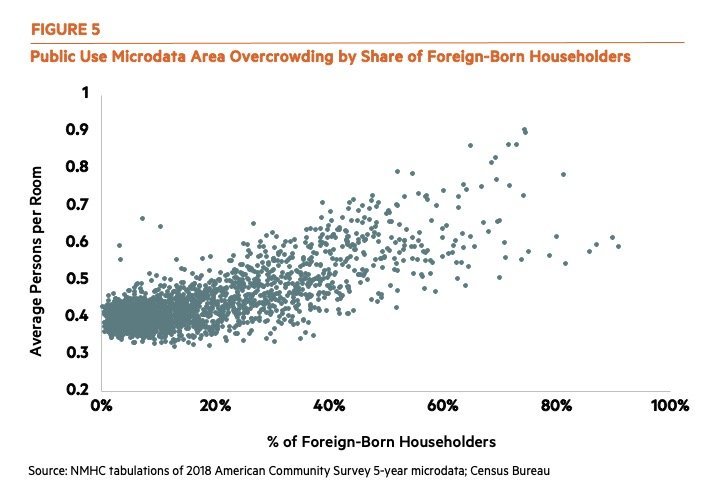

When we plot PUMAs’ average persons per room by their share of foreign-born householders, we see a very strong, positive correlation (see Figure 4). In LA City (Southeast/East Vernon), for example, which we previously identified as having the highest level of overcrowding in the country (0.91 persons per room, on average), 74.4 percent of householders were born outside of the U.S.

But there were PUMAs with much higher shares of foreign-born householders that do not appear on the list of PUMAs with the highest household crowding. South Central Hialeah City and North Central Hialeah City, both of which are in the Miami metro area, were home to 90.1 percent and 90.0 percent foreign-born householders, respectively.

But foreign-born householders are only part of the story. The 2007 HUD study also identified differences in overcrowding rates between citizens and non-citizens, as well as across racial groups. When looking only at white, non-Hispanic, U.S.-born householders, we arrive at a very different list of most-crowded PUMAs. Of the top 10, four were still in the Los Angeles metro area, although we saw much more representation from New York City PUMAs (five of the top 10).

Incomes, Housing Costs and Crowding

Another factor that might explain some of these geographical differences in crowding is income. In theory, we would expect a higher share of lower-income individuals to crowd into smaller quarters to save money on housing. This is, in fact, what we found.

From 2014-2018, there was an average of 0.53 persons per room in households where the householder made less than $15,000 per year, which progressively decreased to an average of 0.49 persons per room with householders making between $15,000 and $29,000, 0.47 persons per room for those making between $30,000 and $59,000, 0.44 persons per room for those earning between $60,000 and $99,000 and 0.41 persons per room for householders making $100,000 or more.

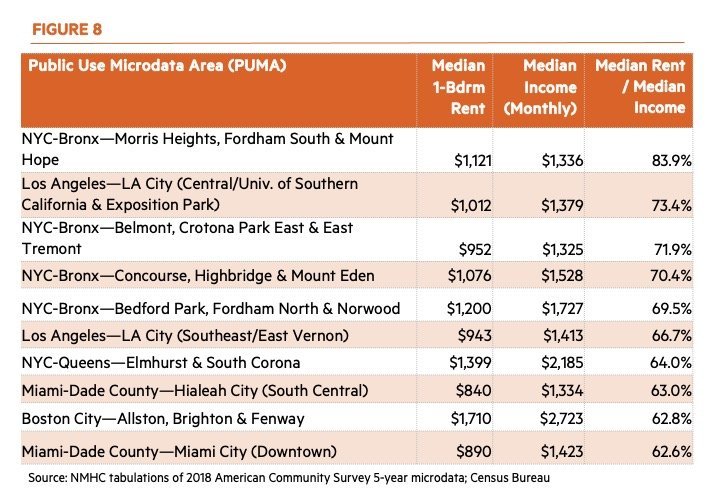

Yet, we cannot look at incomes without also considering the corresponding housing costs. For all U.S. PUMAs, we calculated the ratio of median rent for a one-bedroom rental to the median (monthly) householder income. Of the 10 PUMAs with the highest housing costs relative income, five were in New York City (mostly in the Bronx), two were in Los Angeles, two were in the Miami metro and one was in Boston.

Finally, when we plot each PUMA according to their average persons per room (only households with white, U.S. born householders) and their rent-to-income ratios, we observe a positive correlation (see Figure 9). This suggests that, even after accounting for different rates of crowding across race, citizenship status and immigrant groups, higher housing costs relative to incomes are associated with higher rates of crowding.

Conclusion

Since there is evidence that individuals living in crowded housing situations are more likely to contract COVID-19, it is of public interest to understand what factors contribute to higher levels of crowding in the first place.

We find a very weak correlation between density and household crowding. Southeast/East Vernon, Los Angeles, for instance, had the highest level of household crowding in the U.S., but did not have anywhere close to the level of density found in almost any neighborhood in Manhattan. On the flip side, Manhattan neighborhoods, which are the densest in the country, were only slightly more crowded than the national average, which shows that the benefits of density can be achieved without crowded housing conditions.

Demographics, on the other hand, appear to explain much of the variation in crowding levels across geographies, as white, non-Hispanic, U.S.-born residents tend to live in less crowded households. Yet, even after accounting for varying rates of crowding by race, citizenship status and place of birth, geographies with high housing costs relative to area incomes tended to have higher levels of household crowding. Thus, a lack of affordable housing might contribute not just to a higher share of cost-burdened households but to more crowded housing situations as well.

All of these findings suggest that city dwellers are not inherently a more vulnerable population because they live in more highly populated areas with greater household densities; rather, crowding is arguably a better indicator of potential risk. However, crowding measures are influenced by a wide variety of demographic and economic factors—some of which may reflect personal preferences. That said, there is evidence that markets with greater housing affordability challenges also tend to have more crowded housing arrangements, potentially increasing the risk of viral spread within the community.

Questions or comments on Research Notes should be directed to Chris Bruen, NMHC's Director of Research, at cbruen@nmhc.org or 202/974-2331.